In 2025, the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE) published their vision for the UK NHS ambulance sector, seeking to create a more integrated system of urgent and emergency care.

Dr John Dean (JD), RCP clinical vice president, spoke to AACE’s managing director, Anna Parry (AP), about the relationship between in-hospital physicians and the ambulance service – and how both roles need to evolve to create more integrated, community-based care.

What is the existing relationship between ambulance services and in-hospital physicians?

JD: Traditionally, physicians’ major interaction with ambulances are in an urgent or emergency care setting; in the accident and emergency (A&E) department rather than the wider hospital.

Over the past few years, we've seen more direct interaction between acute medical services and ambulance services – predominantly at the point of receiving patients. More recently, there have been links in same-day emergency care but traditionally, it's been quite a distant relationship.

AP: I'd echo that – it’s the emergency department (ED) interface with ambulance conveyance and handover.

AACE is a membership organisation representing all UK NHS ambulance services. We've often been working against the perception that that the ambulance service only comprises drivers; staff in the ambulance service are clinicians. We're keen to build on that, with ambulance service clinicians working more closely with hospital physicians to ensure the right approach for individual patients.

What are the limitations in the current system?

AP: Working with clinicians within the ambulance service, chief executives and other senior leaders, I have seen things being ‘them and us’ rather than working together. We are much stronger and better together.

The context of current pressure and system demands can exacerbate this feeling. The introduction of the 45-minute maximum handover from NHS England's planning guidance is an example.

Handover delays have been an issue for many years. We've been charting the risk and have studied the harm that occurs for people waiting in the back of and ambulance and waiting in the community.

Where the new guidance is working is in places where ambulance and ED clinicians are talking and collaborating. This takes time, culture, leadership and leaving behind any isolationist approach. Seeing each other's point of view and having dialogue is key; that hasn't always happened historically.

It’s really encouraging to hear examples where that that is happening. The starting point is quite a simple one; that mindset shift is key.

JD: You're absolutely right. The starting point is understanding each other's worlds and the common issue that we're trying to address – and then absolutely keeping the patient's needs at the centre, not the organisation’s or the individual professions’ needs.

AP: The ambulance service is small, but its impact can be massive. If we make a suboptimal decision, the impact is massive. If collectively we can ensure those decisions are the right decisions from the outset, then everybody stands to benefit.

How does the relationship between physicians and the ambulance service need to evolve?

AP: There is work to be done on enhancing relationships between different types of clinician. Together, we make sure that the patient gets the right care in the right place, straight away. That would be more efficient, timely and better for everybody.

JD: How we can talk more, clinician to clinician – taking the trusted assessment of the clinician who is with the patient? Then enable them to access the person who can help make the best decision for that patient.

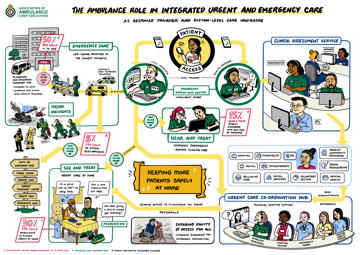

AP: AACE advocates for paramedics to be recognised as trusted assessors, which isn't currently the case. The fundamental components in our AACE vision are navigating people to the right care and working with partners in a multidisciplinary way, managing triage behind the scenes.

In ambulance service control rooms, we have advanced paramedics doing clinical validation and providing remote support to paramedics on scene. Control rooms also link with multidisciplinary teams in unscheduled urgent care co-ordination hubs, which comprise doctors, nurses, palliative care and mental health clinicians, where calls can be pushed or pulled from the stack to ensure the most appropriate response is organised. This may not be an ambulance but possibly an urgent community response team or accessing a hospital physician for remote advice.

JD: It strikes me that these care hubs act as the first line of clinicians – but there might need to be a second line behind that. If you've got a patient with uncontrolled diabetes, the [ambulance] team might need to access a diabetes specialist for advice. Could we create the opportunity for ambulance services addressing acute presentations to link directly to a specialist team who already know a patient?

AP: Absolutely. Ambulance teams bring care to the patient and can facilitate bringing expertise to the patient.

JD: So, [physicians could see] ambulance services as clinical professionals and expert navigators for the patient, incorporating clinical assessment to enable the best navigation. Physicians see emergency physicians working with ambulance services less [than] the wider medical team, but there are examples of that happening. I'm sure people would see the potential benefits.

Having the right people ending up with the right patients in the right place – that's in everybody's best interest.

Anna Parry

AACE managing director

JD: One thing that's impeded this – and is something that health professionals need to work on collectively – is trusted assessment and shared accountability for patients. There’s been caution about taking somebody else's assessment, rather than their own face-to-face assessment of the patient. We need to create a culture where that is better understood and better delivered.

AP: I completely agree, and I appreciate that it's difficult to implement that on a national basis. But it is about seeing things from each other’s perspective and getting back to what is best for the patient. It will require a mindset shift, a different way of working, which needs to be built on a better understanding of each other's position.

The paramedic profession is amazing. We want to move into a space where paramedics work increasingly seamlessly alongside other allied health professionals and specialist experts without any artificial unhelpful barriers.

What is needed to create that evolution?

JD: As professional organisations, we've got a role to be clear that we've moved from individual accountability to shared accountability. We can be clear who has a primary role for that patient in each setting. If we've outlined [ways of working] clearly, as professional standards, then it's much easier for clinicians to work and feel protected.

AP: That feeling of being protected and not going out on a limb, without organisational support, is really important.

JD: A better understanding, early in people's careers, of the knowledge, skills, and capabilities of paramedics is needed. Training [is important], how we enable physicians at an early stage of their careers to understand all members of the professional workforce.

Many physicians are educators; therefore, they might ask about their opportunity to be involved in the training of paramedics because that's one of the ways we build confidence.

AP: We want to ensure that educational institutes use the College of Paramedics curriculum, which seeks to have specialists informing undergraduate courses and training within ambulance services. We are also keen on rotational working, so that paramedics get experience of working directly in other environments. We struggle getting placements within acute settings, but it's absolutely key.

AP: Generally, in the urgent care space, we don’t handle booking next-day appointments other than in relation GP appointments through 111. We could be more nuanced and intelligent about care coordination; linking in with clinicians in hospital to ensure that somebody can get a response in a timely way but without aspiring to get there in minutes or hours. Management of expectations is key because ambulance callouts see – in some instances – a false urgency when having a next-day appointment is appropriate.

How do physicians working with the ambulance service fit into the future of out-of-hospital care?

JD: There is now good evidence that hospital at home can be safe, effective and efficient. The constraints are often workforce-related, sometimes cultural or financial. Increasingly, physicians are working in community-based settings and have been for many years. Community care is well developed in some medical specialties, but there are a lot at the developmental stage.

Supporting urgent community response and providing care in people's homes – particularly around pain in older people, palliative care and respiratory care – are big examples. We're only going to see that grow.

The ambulance service is pivotal and can make a real difference. It isn't about us doing it all. Instead, we seek to coordinate care at a regional level, then work with localised, neighbourhood teams to pass information down.

Anna Parry

AACE managing director

JD: If the ambulance service has a patient with atrial fibrillation and we're able to have a clinical conversation, then many patients (unless they're haemodynamically compromised) wouldn’t need to come to hospital immediately. We have all seen patients like that, who are in hospital because we currently aren’t able to enact the right clinical dialogue. We can’t transfer our knowledge to the expert in the patient’s home.

We're still at early-stage development in the broader thinking about how we can be much more connected with technology. Physicians don't have to be in the same place as the patient – we can do much more with remote advice to other professionals, who might be in that patient's home.

AP: That has made such a profound difference. It can be much better to care for a patient remotely in their home , rather than pulling them into the hospital.

JD: There is the sharing of expertise and knowledge that ambulance services and paramedics have – and bringing that to physician leaders, to really explore what the opportunities are.

What might be the limitations that we face in community-based care?

JD: The aim is providing the most appropriate care, for that patient, in the best environment. There is a secondary benefit of reducing pressure in hospital – but it is important that the reason for community care is not crowding in hospitals, but that it’s the right thing to do for the patient.

AP: We know how difficult things are in EDs right now; any move to reduce hospital bed numbers needs to be undertaken carefully, rather than just taking beds out. If we can get to a position whereby care can be provided in the community in a reliable, sustainable, funded way – that's preferable. But we certainly wouldn't advocate taking out provision, unless other provision is available.

We have to ensure that we're mindful of health inequalities. We see certain cohorts within the population being more regular users of emergency services. It is important to understand inequalities to ensure that those individuals get the most appropriate care. AACE does a lot of work around health inequalities and we should share that, so we can ensure that patient groups are getting appropriate care – and we can understand our service users better. We need to spend time looking at the data, so we can seek to do better for areas of the population whose needs we're not currently meeting in the best way.

As soon as you get the wrong patient in hospital, it starts an unhelpful chain of events. Long, extended hospital stays are usually not in the patient's best interest, unless they need to be there.