As she celebrates her daughter’s graduation and becoming an F1, Namita shares the story of the three generations in her family who have dedicated their lives to practising medicine.

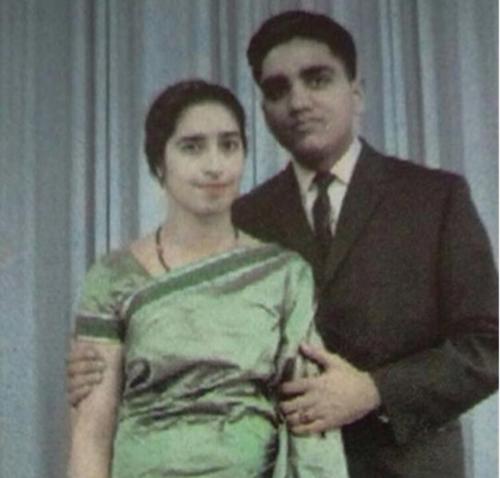

My parents came to the UK, as many doctors of their generation did, at the invitation of the British government. Both were impacted by partition in 1947, my father’s family very significantly. Despite that, they came to the UK for postgraduate medical study and to see the world. There are some great stories of how they went camping round Europe in the late 60s! I arrived right at the end of that decade and my sister a couple of years later.

We all know how hard it is to raise a family, work and study. It was even harder then. My mum was told that she was a woman and not white, she would be better off returning to India. This kind of careers advice, we know, is still given today over 50 years later, fortunately far less often.

My father also faced hurdles during his career because of his race, and he never got his MRCP. Despite his challenges, he did find great job satisfaction as a GP and my mum worked as a consultant radiologist.

The injustice that they faced was one of the main drivers for my interest in medical education. I faced many of the issues that they did, and I wanted to make things better, change the system if I could. We have a phrase for it now, ‘differential attainment’, but even in my time of exam-taking I often received a shrug of the shoulders from senior doctors when I told them that I had failed again. Real support and sensible advice were hard to find.

The definition of differential attainment has blurred to include all variability, not just that which we would not have expected. That is making it harder to address, but collectively we are. I think we do now have a more transparent system, where at least exams have curricula, candidates get feedback and there is increasing understanding of individual exam support required. Induction has dramatically improved for all graduates and new starters, especially those who qualified internationally from different healthcare systems.

Discrimination has and always will exist, and the current demonstrations across England once again show the best and worst of us. Those of us who do work and lead in this area need to be inclusive of everyone, not just focus on our own individual protected characteristics.

My father loved medicine – he always said that it was the best career in the world and if you were able to, why wouldn’t you be a doctor? My mother taught us about doing a job that used your mind and being able to look after and support yourself. Make your own decisions and even if it’s the wrong one, you did the best you could at the time.

The legacy of my parents is impressive. Both were the first doctors in their respective families, both of their daughters are doctors with senior leadership roles, and now my daughter has just started as an F1. My mother and I were able to be at her graduation and I am sure that my father was watching from somewhere, very proud with tears in his eyes.

Is it in the blood? Or was he just better at convincing everyone what a fantastic career medicine is and what a privilege it is to practise as a doctor? I suppose we will know if there is another generation to follow.

Prof Namita Kumar

MBChB MD MMEd FRCP FAcadMEd

Regional postgraduate dean NHSE NEY

Co-chair NHSE postgraduate deans

National dean for PGMDE risk and business oversight

RCP councillor and trustee councillor 2017–22